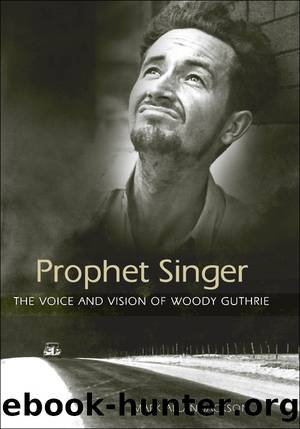

Prophet Singer by Mark Allan Jackson

Author:Mark Allan Jackson

Language: eng

Format: epub

Publisher: University Press of Mississippi

Published: 2007-03-14T16:00:00+00:00

A stylized image of numerous lynching victims hanging from a bridge with a wasted city set in the distance, c. 1946. Sketch by Woody Guthrie. Courtesy of the Ralph Rinzler Archives.

The connection between the Nelsonsâ end and his lyrics becomes much more certain in the song âSlipknot.â Here, the narrator twice asks, âDid you ever lose a brother in that slipknot?â Then comes the answer, âYes. My brother was a slave ⦠he tried to escape, / And they drug him to his grave with a slipknot.â This question and answer pattern is repeated in the second verse:

Did you ever lose your father on that slipknot?

Did you ever lose your father on that slipknot?

Yes, they hung him from a pole anâ they shot him full of holes

And they left him hang to rot in that slipknot.99

As noted by Oklahoma folklorist Guy Logsdon, âThe power of this song indicates how far [Guthrie] had come in his idea about race relations and how deeply he felt about the evil of lynching.â100 But by only looking at the lyrics, you would find no specific trace of the Nelsonsâ murder. However, an endnote to this song does directly reference this incident when Guthrie writes, âDedicated to the many negro mothers, fathers, and sons alike, that was lynched and hanged under the bridge of the Canadian River, seven miles south of Okemah, Okla., and to the day when such will be no more.â101 Obviously, he sees his antilynching work as a way to rectify the wrong that occurred in his hometown.

Other moments from Guthrieâs writing directly reference the Nelsonsâ deaths. Among its other invocations of Guthrieâs youth, the autobiographical song âHigh Balladreeâ offers this striking remembrance:

A nickle post card I buy off your rack

To show you what happens if youâre black and fight back

A lady and two boys hanging down by their necks

From the rusty iron rigs of my Canadian bridge.102

Here, the postcard referenced earlier appears in full, just as he remembered it. But of all Guthrieâs antilynching songs, âDonât Kill My Baby and My Sonâ (also titled âOld Dark Townâ and âOld Rock Jailâ) most fully re-creates the Nelsonsâ end.

In this song, the narrator returns to âthe old dark town ⦠where I was bornâ and almost immediately hears âthe lonesomest sounding cry / That I ever had heard.â Investigating, he discovers âa black girl pulling her hairâ in jail and hears her lament, which becomes the songâs chorus:

Donât let them kill my baby,

And donât let them kill my son!

You can hang me by my neck

On that Canadian Riverâs bridge!

Donât let them kill my baby and my son!

In another verse, we find that she sits in jail and faces death because âA bad man had pulled his gun / To make her hide him away.â Soon after these revelations, the narrator walks into a store and finds a disturbing scene on a postcard: âI saw my Canadian Riverâs bridge, / Three bodies swung in the wind.â As he stares at the card, he hears her mercy plea once again.

Download

This site does not store any files on its server. We only index and link to content provided by other sites. Please contact the content providers to delete copyright contents if any and email us, we'll remove relevant links or contents immediately.

Einstein: His Life and Universe by Walter Isaacson(1984)

Finding Freedom: Harry and Meghan and the Making of a Modern Royal Family by Omid Scobie & Carolyn Durand(1367)

Promised Land (9781524763183) by Obama Barack(1323)

Finding Freedom by Omid Scobie(1270)

Compromised by Peter Strzok(1242)

JFK by Fredrik Logevall(1135)

Freedom by Sebastian Junger(837)

The Russia House by John Le Carré(798)

Salford Lads: The Rise and Fall of Paul Massey by Bernard O'Mahoney(749)

The Irish Buddhist by Alicia Turner(741)

Day of the Dead by Mark Roberts(738)

Kremlin Winter by Robert Service(695)

Graveyard (Ed & Lorraine Warren Book 1) by Ed Warren & Lorraine Warren & Robert David Chase(693)

A World Ablaze by Craig Harline(687)

Joe Biden: American Dreamer by Evan Osnos(657)

Flying Tiger by Samson Jack(649)

100 Things Successful Leaders Do by Nigel Cumberland(626)

Melania and Me: The Rise and Fall of My Friendship With the First Lady by Stephanie Winston Wolkoff(625)

The Mission by David W. Brown(613)